Schizophrenia (originated from the Greek word schizein meaning "to split" and phrēn, "mind") is a psychiatric diagnosis that describes a mental disorder characterized by abnormalities in the perception or expression of reality. It most commonly manifests as auditory hallucinations, paranoid or bizarre delusions, or disorganized speech and thinking with significant social or occupational dysfunction. Schizophrenia is a severe, lifelong, disabling brain disorder. People who have it may hear voices, see things that aren't there or believe that others are reading or controlling their minds. Onset of symptoms typically occurs in young adulthood, with approximately 0.4–0.6% of the population affected. In men, symptoms usually start in the late teens and early 20s. While in women, they start in the mid-20s to early 30s. Other symptoms include

No one is sure what causes schizophrenia, but your genetic makeup and brain chemistry probably play a role. Studies suggest that genetic and environmental factors can act in combination to result in schizophrenia. Evidence suggests that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has a significant heritable component but that onset is significantly influenced by environmental factors or stressors.

Several factors may contribute to schizophrenia, including:

Studies have suggested a high level of heritability of schizophrenia. It is a condition of complex inheritance, with several genes possibly interacting to generate risk for schizophrenia or the separate components that can co-occur leading to a diagnosis. These genes appear to be non-specific, in that they may raise the risk of developing other psychotic disorders such as bipolar disorder. Rare deletions or duplications of tiny DNA sequences within genes (known as copy number variants) may be linked to increased risk for schizophrenia.

One curious finding is that people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring, (at least in the northern hemisphere). There is now evidence that prenatal exposure to infections increases the risk for developing schizophrenia later in life, providing additional evidence for a link between in utero developmental pathology and risk of developing the condition.

Social disadvantage has been found to be a risk factor, such as poverty and migration related to social adversity, racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment or poor housing conditions. Childhood experiences of abuse or trauma have also been implicated as risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life. Parenting is not held responsible for schizophrenia but unsupportive dysfunctional relationships may contribute to an increased risk.

About half of all patients with schizophrenia abuse drugs or alcohol. The two most often used explanations for this are "substance use causes schizophrenia" and "substance use is a consequence of schizophrenia", and they both may be correct. Relatively strong evidence based on multiple studies suggests that cannabis may play a role in the development of schizophrenia. However, there is no sufficient evidence for the role alcohol or other drugs. On the other hand, that people with schizophrenia are known to use drugs to alleviate the depression, anxiety and loneliness resulting from their disorder.

A number of psychological mechanisms have been implicated in the development and maintenance of schizophrenia. Cognitive biases that have been identified in those with a diagnosis or those at risk, especially when under stress or in confusing situations, include excessive attention to potential threats, jumping to conclusions, making external attributions, impaired reasoning about social situations and mental states, difficulty distinguishing inner speech from an external source, and difficulties with early visual processing and maintaining concentration. Some cognitive features may reflect global neurocognitive deficits in memory, attention, problem-solving, executive function or social cognition, while others may be related to particular issues and experiences. Despite a common appearance of "blunted affect", recent findings indicate that many individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are highly emotionally responsive, particularly to stressful or negative stimuli, and that such sensitivity may cause vulnerability to symptoms or to the disorder. Some evidence suggests that the content of delusional beliefs and psychotic experiences can reflect emotional causes of the disorder, and that how a person interprets such experiences can influence symptomatology. The use of "safety behaviors" to avoid imagined threats may contribute to the chronicity of delusions. Further evidence for the role of psychological mechanisms comes from the effects of therapies on symptoms of schizophrenia.

Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as MRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus, and temporal lobes. These differences have been linked to the neurocognitive deficits often associated with schizophrenia.

Role of change in neurotransmitters dopamine and glutamate have found in schizophrenia because the drugs affecting these neurotransmitters produces symptoms mimicking with schizophrenia. The "dopamine theory of schizophrenia" states that schizophrenia is caused by an overactive dopamine system in the brain.

TYPES OF SCHIZOPHRENIA:

THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF SCHIZOPHRENIA ARE AS FOLLOWS

1. Paranoid-type schizophrenia: This is characterized by delusions and auditory hallucinations but relatively normal intellectual functioning and expression of affect. The delusions can often be about being persecuted unfairly or being some other person who is famous. People with paranoid-type schizophrenia can exhibit anger, aloofness, anxiety, and argumentativeness.

2. Disorganized type /hebephrenic schizophrenia: This is characterized by speech and behavior that are disorganized or difficult to understand, and flattening or inappropriate emotions. People with disorganized-type schizophrenia may laugh at the changing color of a traffic light or at something not closely related to what they are saying or doing. Their disorganized behavior may disrupt normal activities, such as showering, dressing, and preparing meals.

3. Catatonic-type schizophrenia: This is characterized by disturbances of movement. People with catatonic-type schizophrenia may keep themselves completely immobile or move all over the place. They may not say anything for hours, or they may repeat anything you say or do senselessly. Either way, the behavior is putting these people at high risk because it impairs their ability to take care of themselves.

4. Undifferentiated-type schizophrenia: This is characterized by some symptoms seen in all of the above types but not enough of any one of them to define it as another particular type of schizophrenia.

5. Residual-type schizophrenia: This is characterized by a past history of at least one episode of schizophrenia, but the person currently has no positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech or behavior). It may represent a transition between a full-blown episode and complete remission, or it may continue for years without any further psychotic episodes.

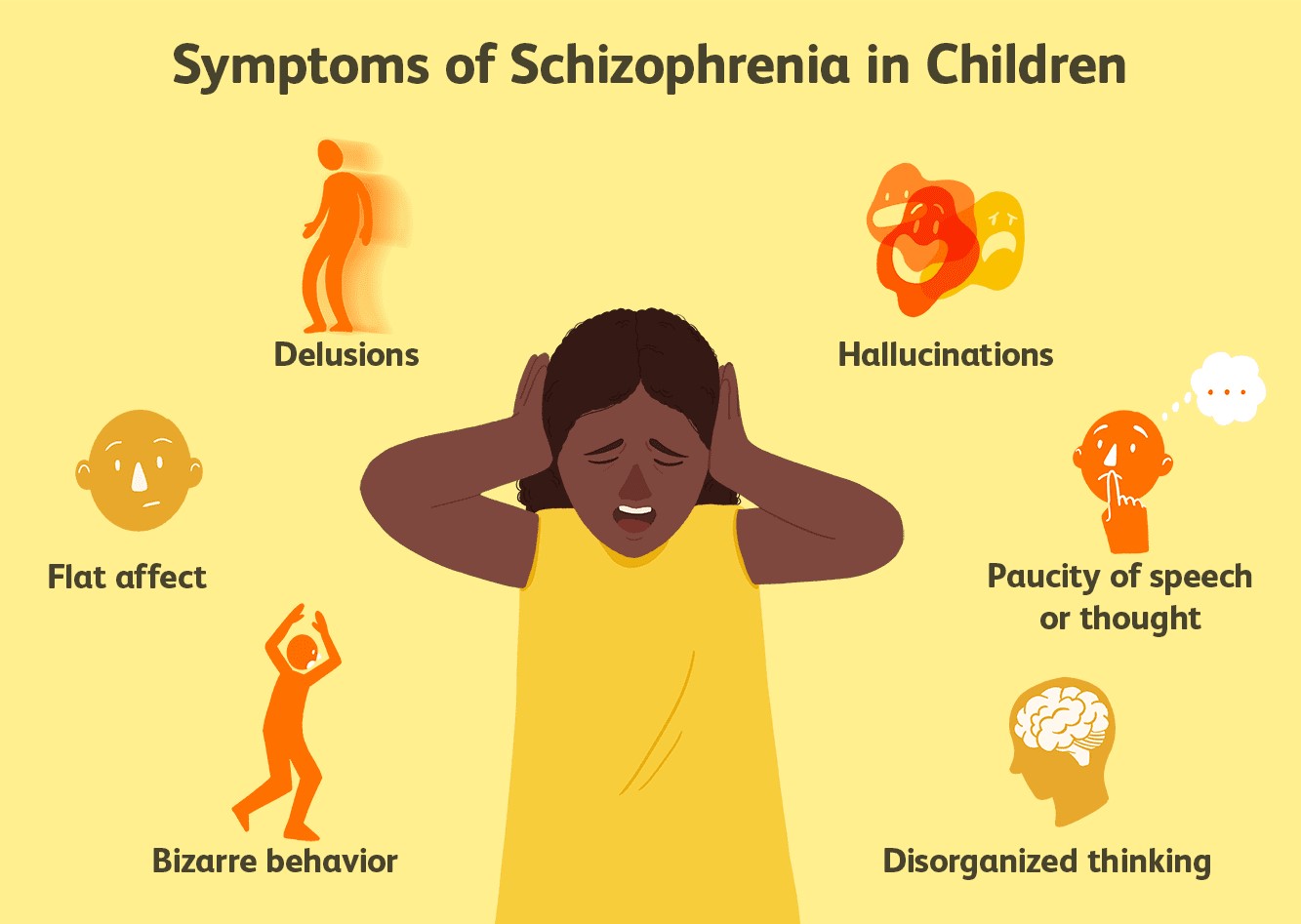

Symptoms of schizophrenia:

Schizophrenia symptoms range from mild to severe. There are three main types of symptoms.

1. Positive symptoms refer to a distortion of a person's normal thinking and functioning. They are "psychotic" behaviors. People with these symptoms are sometimes unable to tell what's real from what is imagined. Positive symptoms include:

2. Negative symptoms refer to difficulty showing emotions or functioning normally. When a person with schizophrenia has negative symptoms, it may look like depression. People with negative symptoms may:

3. Cognitive symptoms are not easy to see, but they can make it hard for people to have a job or take care of themselves. Cognitive symptoms include:

Teens can get schizophrenia, but it may be hard to see at first. This is because the symptoms may look like problems many teenagers have. A teen developing schizophrenia may:

Course

Schizophrenia usually starts between the late teens and the mid-30s, whereas onset prior to adolescence is rare (although cases with age at onset of 5 or 6 years have been reported). Schizophrenia can also begin later in life (e.g., after age 45 years), but this is uncommon. Usually the onset of Schizophrenia occurs a few years earlier in men than women. The onset may be abrupt or insidious. Usually Schizophrenia starts gradually with a prepsychotic phase of increasing negative symptoms (e.g., social withdrawal, deterioration in hygiene and grooming, unusual behavior, outbursts of anger, and loss of interest in school or work). A few months or years later, a psychotic phase develops (with delusions, hallucinations, or grossly bizarre/disorganized speech and behavior). Individuals who have an onset of Schizophrenia later in their 20's or 30's are more often female, have less evidence of structural brain abnormalities or cognitive impairment, and display a better outcome. Schizophrenia usually persists, continuously or episodically, for a life-time. Complete remission (i.e., a return to full premorbid functioning) is uncommon. Some individuals appear to have a relatively stable course, whereas others show a progressive worsening associated with severe disability.

Co-morbidity

Alcoholism and drug abuse worsen the course of this illness, and are frequently associated with it. From 80% to 90% of individuals with Schizophrenia are regular cigarette smokers. Anxiety and phobias are common in Schizophrenia, and there is an increased risk of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Panic Disorder. Schizotypal, Schizoid, or Paranoid Personality Disorder may sometimes precede the onset of Schizophrenia.

Complications

Individuals with this disorder may develop significant loss of interest or pleasure. Likewise, some may develop mood abnormalities (e.g., inappropriate smiling, laughing, or silly facial expressions; depression, anxiety or anger). Often there is day-night reversal (i.e., staying up late at night and then sleeping late into the day). The individual may show a lack of interest in eating or may refuse food as a consequence of delusional beliefs. Often movement is abnormal (e.g., pacing, rocking, or apathetic immobility). Frequently there are significant cognitive impairments (e.g., poor concentratiion, poor memory, and impaired problem-solving ability). The majority of individuals with Schizophrenia are unaware that they have a psychotic illness. This poor insight is neurologically caused by illness, rather than simply being a coping behavior. This is comparable to the lack of awareness of neurological deficits seen in stroke. This poor insight predisposes the individual to noncompliance with treatment and has been found to be predictive of higher relapse rates, increased number of involuntary hospitalizations, poorer functioning, and a poorer course of illness. Depersonalization, derealization, and somatic concerns may occur and sometimes reach delusional proportions. Motor abnormalities (e.g., grimacing, posturing, odd mannerisms, ritualistic or stereotyped behavior) are sometimes present.

Life Expectancy: The life expectancy of individual with Schizophrenia is shorter than that of the general population for a variety of reasons. Suicide is an important factor, because approximately 10% of individuals with Schizophrenia commit suicide - and between 20% and 40% make at least one suicide attempt. There is an increased risk of assaultive and violent behavior. The major predictors of violent behavior are male gender, younger age, past history of violence, noncompliance with antipsychotic medication, and excessive substance use. However, it should be noted that most individuals with Schizophrenia are not more dangerous to others than those in the general population.

Diagnostic

Diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of the person, and abnormalities in behavior reported by family members, friends or co-workers, followed by a clinical assessment by a psychiatrist, social worker, clinical psychologist or other mental health professional. Psychiatric assessment includes a psychiatric history and some form of mental status examination.

To diagnose schizophrenia, one has first to rule out any medical illness that may be the actual cause of the behavioral changes. Once medical causes have been looked for and not found, a psychotic illness such as schizophrenia could be considered. The diagnosis will best be made by a licensed mental health professional (preferably a psychiatrist) who can evaluate the patient and carefully sort through a variety of mental illnesses that might look alike at the initial examination.

Diagnostic Tests

No laboratory test has been found to be diagnostic of this disorder. However, individuals with Schizophrenia often have a number of (non-diagnostic) neurological abnormalities. They have enlargement of the lateral ventricles, decreased brain tissue, decreased volume of the temporal lobe and thalamus, a large cavum septum pellucidi, and hypofrontality (decreased blood flow and metabolic functioning of the frontal lobes). They also have a number of cognitive deficits on psychological testing (e.g., poor attention, poor memory, difficulty in changing response set, impairment in sensory gating, abnormal smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements, slowed reaction time, alterations in brain laterality, and abnormalities in evoked potential electrocephalograms).

The doctor will examine someone in whom schizophrenia is suspected either in an office or in the emergency department. The doctor's role is to ensure that the patient doesn't have any medical problems. The doctor takes the patient's history and performs a physical examination. Laboratory and other tests, sometimes including a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the brain, are performed. Physical findings can relate to the symptoms associated with schizophrenia or to the medications the person may be taking.

WHEN TO SEEK MEDICAL CARE

If someone who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia has any behavior change that might indicate treatment is not working, it is best to call the doctor. If the family, friends, or guardians of a person with schizophrenia believe symptoms are increasing, a doctor should be called as well. Do not overlook the possibility of another medical problem in addition to the schizophrenia.

Treatment of schizophrenia

There is no cure for schizophrenia. But two main types of treatment can help control symptoms: medication and psychosocial treatments.

1. Medication. Medicines can relieve many of the symptoms, but it can take several tries before you find the right drug. You can reduce relapses by staying on your medicine for as long as your doctor recommends. With treatment, many people improve enough to lead satisfying lives. Several homeopathic medicines are found useful to lessen the symptoms of schizophrenia.

Side effects of antipsychotic drugs:

An allopathic medication causes lots of side effects. Patients should always tell their doctor about these problems. Side effects include:

1. Homeopathic Treatment: Homeopathic medication doesn’t produce any kind of side effect and can lead a schizophrenic to complete recovery from the symptoms if given properly and at appropriate time, till there is no gross pathological change. Medicines commonly indicated in psychotic disorders are- Hyoscymus, Stramonium, Chlorpromazine, Haloperidol, Anhalonium levinii, Kali brom, Cannabis indica, Ignatia, Nat mur, Calcarea Carb, Mancenella, Anacardium, Cortico, Reserpine, Carcinosin, Germanium met, Thuja, Phosphorus, Veratrum alb etc.

2. Psychosocial treatments. These treatments help patients deal with their illness from day to day. The treatments are helpful after patients find a medication that works. Treatments include:

Ways to Speed Recovery and to Prevent Recurrence

There will be a fair amount of uncertainty about causes and outcome, but providing treatment quickly and early has been shown definitively to greatly improve prospects and outcome.

• Believe in your power to affect the outcome: you can.

• Make forward steps cautiously, one at a time. Go slow. Allow time for recovery. Recovery takes time. Rest is important. Things will get better in their own time. Build yourself up for the next life steps.

• Consider using medication to protect your future. A little goes a long way. The medication is working and is necessary even if you feel fine. Work with your doctor to find the right medication and the right dose. Have patience, it takes time. Take medications as they are prescribed. Take only medications that are prescribed.

• Try to reduce your responsibilities and stresses, at least for the next six months or so.

• Take it easy. Use a personal yardstick. Compare this month to last month rather than last year or next year.

• Use the symptoms as indicators. If they reappear, slow down, simplify and look for support and help, quickly. Learn and use your early warning signs and changes in symptoms. Consult with your family clinician or psychiatrist. Anticipate stresses.

• Create a protective environment

• Keep it cool. Enthusiasm is normal. Tone it down. Disagreement is normal. Tone it down too.

• Give each other space. Time out is important for everyone. It's okay to reach out. It's okay to say "no".

• Observe limits. Everyone needs to know what the rules are. A few good rules keep things clear.

• Ignore what you can't change. Let some things slide. Don't ignore violence or concerns about suicide.

• Keep it simple. Say what you have to say clearly, calmly and positively.

• Carry on business as usual. Reestablish family routines as quickly as possible. Stay in touch with family and friends.

• Solve problems step by step. Make changes gradually. Work on one thing at a time. Look for coping methods that work for you, and work with your clinicians to find other methods when yours don't work.

• Watch for large reactions to even little changes in relationships. Have a plan for what to do and where to get help. Don't get too vigilant.

• Keep a regular sleep and wake cycle. Don't fly more than four time zones in one day. Avoid night shift or rotating shift jobs. Don't do all-nighters, for work or play.

• Keep a balanced life and a balanced perspective.

• Keep up an outside occupation, but don't work too hard for a while.

• Take time to cool out. If it's in your nature, use Zen or other meditation techniques to keep stress, strain and anxiety to a minimum.

• Watch out for the effects of street drugs and alcohol. They make symptoms worse and may cause relapse.

• Never use cocaine, amphetamines ("speed") or hallucinogens at all for any reason. Avoid over-the-counter stimulants like pseudoephedrine, diet pills, No-Doze, and inhalants. They're internal stimulants and can cause biologically rapid onset of psychosis. Keep alcohol to a bare minimum, or use not at all if possible.

• Stay away from nicotine and caffeine, as hard as that might be.

• Explain your circumstances to your closest relatives and friends, and ask them to help and stand by you.

• Learn to accept support from your network of family and friends.

• Don't move abruptly or very far from your family home or home town until this period passes and stability returns. If you have to move prepare well in advance.

• Dodge the bad scenes and look for the good ones.

• Keep a social network intact and try not to change it without lots of preparation.

• Decide who you want to know about your situation. You may have to play the system to protect yourself.

• Keep hope alive.

Tips for Helping People who have Schizophrenia

If you have a family member with mental illness, remember these points:

1. You cannot cure a mental disorder for a family member.

2. Despite your efforts, symptoms may get worse, or may improve.

3. If you feel much resentment, you are giving too much.

4. It is as hard for the individual to accept the disorder as it is for other family members.

5. Acceptance of the disorder by all concerned may be helpful, but not necessary.

6. A delusion will not go away by reasoning and therefore needs no discussion.

7. You may learn something about yourself as you learn about a family member's mental disorder.

8. Separate the person from the disorder. Love the person, even if you hate the disorder.

9. Separate medication side effects from the disorder/person.

10. It is not OK for you to be neglected. You have needs & wants too.

11. Your chances of getting mental illness as a sibling or adult child of someone with NBD are 10-14%. If you are older than 30, they are negligible for schizophrenia.

12. Your children's chances are approximately 2-4%, compared to the general population of 1%.

13. The illness of a family member is nothing to be ashamed of. Reality is that you may encounter discrimination from an apprehensive public.

14. No one is to blame.

15. Don't forget your sense of humor.

16. It may be necessary to renegotiate your emotional relationship.

17. It may be necessary to revise your expectations.

18. Success for each individual may be different.

19. Acknowledge the remarkable courage your family member may show dealing with a mental disorder.

20. Your family member is entitled to his own life journey, as you are.

21. Survival-oriented response is often to shut down your emotional life. Resist this.

22. Inability to talk about feelings may leave you stuck or frozen.

23. The family relationships may be in disarray in the confusion around the mental disorder.

24. Generally, those closest in sibling order and gender become emotionally enmeshed, while those further out become estranged.

25. Grief issues for siblings are about what you had and lost. For adult children the issues are about what you never had.

26. After denial, sadness, and anger comes acceptance. The addition of understanding yields compassion.

27. The mental illnesses, like other diseases, are a part of the varied fabric of life.

28. Shed neurotic suffering and embrace real suffering.

29. The mental illnesses are not on a continuum with mental health. Mental illness is a biological brain disease.

30. It is absurd to believe you may correct a physical illness such as diabetes, the schizophrenias, or manic-depression with talk, although addressing social complications may be helpful.

31. Symptoms may change over time while the underlying disorder remains.

32. The disorder may be periodic, with times of improvement and deterioration, independent of your hopes or actions.

33. You should request the diagnosis and its explanation from professionals.

34. Schizophrenia may be a class of disorders rather than a single disorder.

35. Identical diagnoses does not mean identical causes, courses, or symptoms.

36. Strange behavior is symptom of the disorder. Don't take it personally.

37. You have a right to assure your personal safety.

38. Don't shoulder the whole responsibility for your mentally disordered relative.

39. You are not a paid professional case worker. Work with them about your concerns.

Maintain your role as the sibling, child, or parent of the individual. Don't change your role.

40. Mental health professionals, family members, & the disordered all have ups and downs when dealing with a mental disorder.

41. Forgive yourself and others for mistakes made.

42. Mental health professionals have varied degrees of competence.

43. If you can't care for yourself, you can't care for another.

44. You may eventually forgive your member for having MI.

45. The needs of the ill person do not necessarily always come first.

46. It is important to have boundaries and set clear limits.

47. Most modern researchers favor a genetic, biochemical (perhaps interuteral), or viral basis. Each individual case may be one, a combination, or none of the above.

Genetic predisposition may result from a varied single gene or a combination.

48. Learn more about mental disorders.

49. From Surviving Schizophrenia: "Schizophrenia randomly selects personality types, and families should remember that persons who were lazy, manipulative, or narcisstic before they got sick are likely to remain so as schizophrenic." And, "As a general rule, I believe that most persons with schizophrenia do better living somewhere other than home. If a person does live at home, two things are essential--solitude and structure." And, "In general, treat the ill family member with dignity as a person, albeit with a brain disease." And, "Make communication brief, concise, clear and unambiguous."

50. It may be therapeutic to you to help others if you cannot help your family member.

51. It is recognizing that a person has limited capabilities should not mean that you expect nothing of them.

52. Don't be afraid to ask your family member if he is thinking about hurting himself.

A suicide rate of 10% is based on it happening to real people. Your own relative could be one. Discuss it to avoid it.

53. Mental disorders affect more than the afflicted.

54. Your conflicted relationship may spill over into your relationships with others. You may unconsciously reenact the conflicted relationship.

55. It is natural to experience a cauldron of emotions such as grief, guilt, fear, anger, sadness, hurt, confusion, etc. You, not the ill member, are responsible for your own feelings.

56. Eventually you may see the silver lining in the storm clouds: increased awareness, sensitivity, receptivity, compassion, maturity and become less judgmental, self-centered.

57. Allow family members to maintain denial of the illness if they need it. Seek out others whom you can talk to.

58. You are not alone. Sharing your thoughts and feelings with others in a support group is helpful and enlightening for many.

59. The mental disorder of a family member is an emotional trauma for you. You pay a price if you do not receive support and help.

60. Go Slow. Recovery takes time. Rest is important. Things will get better in their own time

61. Less Stimulation. Keep it cool. Enthusiasm is normal. Tone it down! Disagreement is normal. Tone it down, too!

62. Set limits and have structure. Everyone needs to know what the rules are. A few good rules keep things calmer.

63. Let some things slide. Ignore what you can't change. Don't ignore violence!

64. Keep it simple. Say what you have to say clearly, calmly and positively.

65. See that Dr's. orders are followed. Take medications as they are prescribed. Take only medication that is prescribed.

66. Socialize and carry on business as usual. Reestablish family routines quickly as possible. Stay in touch with family and friends. Take vacations.

67. No street drugs or alcohol. They make symptoms worse.

68. Pick up on early signs of relapse. Note changes such as inappropriate fear, annoyance, etc.

69. Solve problems step by step. Make changes gradually. Work on one thing at a time.

70. Lower expectations, temporarily. Use a personal yardstick. Compare this month to last month rather than last year or next year.